Light Rail Now/Light Rail Progress can be contacted at: Light Rail Now! |

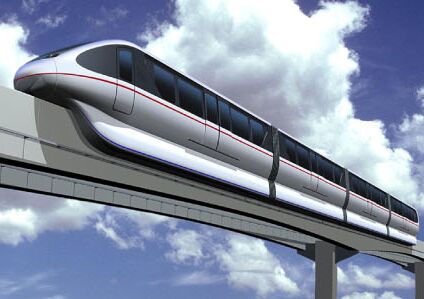

Monorail advocates often make claims about the low installation costs of monorail systems, particularly compared to light rail transit (LRT) and other standard rail transit systems. For example, Seattle's Rise Above it All pro-monorail group claims, "The Monorail is less expensive to build than other transit because it uses public right of ways and no tunneling is necessary – and won't close streets during construction." Often, these claims are based on "theoretical" estimates and the sales pitches of monorail vendors eager to market their products. But what does real-world experience tell us about the actual costs of monorail systems, and how that compares with the costs of LRT? Comprehensive and reliable cost data are essential for evaluating monorail and any other potential alternative transit modes for US urban areas. Data drawn from actual experience, and, in some cases, from highly reliable projections, are generally judged to be the most accurate for competent analyses. To a considerable extent, much of the available data in terms of real-world experience with monorail technology comes from Japan. This is logical, since Japan is undoubtedly the world leader in monorail implementation, with more urban revenue systems than any other country. The following capital and construction cost data in Table 1 have been drawn from such sources. For consistency, all data have been escalated to year 2002 dollars using CPI data from the US Department of Commerce, thus enabling a fair comparison of per-mile costs for systems built in widely different years. Table 1.

While the Kuala Lumpur monorail exhibits substantially lower per-mile costs than most of those cited above in Table 1, those costs should not be considered typical of capital costs which would be experienced in the development of such a system in the United States or other advanced industrialized countries, where the substantially lower, Third World-level construction labor and other lower costs available in Malaysia would not be available. (For example, according to the CIA World Factbook, Malaysia had a per-capita GDP of $9,000 in 2001, about equal to that of Mexico, but only one third of Japan's and 1/4 that of the USA.)

Likewise, a drip pan beneath the beamways would be necessary where the monorail would be routed over public roadway and pedestrian areas. (in the photo of the Las Vegas monorail project above, one should note that cable trays have apparently not been installed in this section, nor is there any plan for a drip pan beneath the beamways, which are predominantly not routed over pedestrian or other public traffic areas.) These structural elements would undoubtedly impact visual and aesthetic characteristics of any monorail. While the Kuala Lumpur monorail is narrower in cross-section

than a comparable US monorail would be, a mandatory

evacuation walkway and cable trays would surely widen the lateral

dimension of any US elevated fixed-guideway structure. Another limitation of the Kuala Lumpur monorail system would seem to be

constrained capacity. The monorail appears to have significantly

lower capacity than most LRT systems – even surface-routed

LRT, which, with 3-car trains at 3-minute headways, could provide

capacity of about 9,000 passengers per hour per direction

(pphpd). in contrast, the Malaysian project is installing a

light-capacity system with short, 21-meter-long, 2-unit trainsets

and relatively short-platform stations. Even with a 2-minute

headway, the capacity of the Kuala Lumpur system, using

tolerable US loading standards, would be approximately 2,800

pphpd – about 31% of a surface LRT line. This light capacity

undoubtedly also helps explain the seemingly low cost of the

Kuala Lumpur project. With regard to the current privately financed monorail project of

the Las Vegas Monorail Corporation, an official of the Las Vegas

Regional Transportation Commission reports that slightly over

$600 million in bonds backed by the State of Nevada have been

sold to construct and finance the initial project. For the 3.6-mile

system, that amounts to about $167 million per mile. Capital costs of recent LRT projects, again, drawn from actual project experiences, are listed in Table 2. Table 2.

From these tables, some broad conclusions can be drawn. in regard to monorail systems, it can be seen that, with an average capital cost of nearly $140 million per mile, and with some individual systems exceeding $200 million per mile, these examples of monorail systems do not seem to corroborate the low-cost claims of many monorail promoters. Furthermore, these costs hardly bear out assertions that monorails are roughly equivalent in cost to LRT. Monorail advocates often argue that the ostensibly simpler beam

guideways (beamways) for monorails may, on average, cost less

than the support deck and trackage for an elevated dual-steel-rail

system (which requires the addition of rail structure above the

beamways). However, this cost advantage is probably offset by other

limitations. For example, monorail switches appear to entail more

complicated machinery, and have a significantly higher cost –

about 15 times the cost of an ordinary railway switch, according to

a recent study. By far the greatest cost liability of monorails relates to their greatest inflexibility – their need to be built entirely grade-separated in some fashion, usually elevated. Even for comparatively small, light-capacity monorails, this means relatively huge, elevated stations, with elevators and, especially for higher-traffic locations, escalators. As a result of these and other factors, the data in Tables 1 and 2 above clearly suggest that monorail systems tend to average about 5-6 times the cost of predominately surface-routed LRT. Even compared to LRT systems with extensive civil works, like tunnels, subways, elevated structures, and viaducts, monorail costs still seem to average more. For cities selecting a preferred mode for regional rail transit development, this implies that investing in monorail technology means much less system spread, and less ridership, for available resources. Light Rail Progress wishes to extend particular thanks to Leroy W. Demery, Jr. for some information used in this report. Light Rail Progress Rev. 2002/11/24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||