Light Rail Progress can be contacted at: Light Rail Progress |

The following historical analysis by Mary Beth Callie, an adjunct professor at the University of Arizona, contributes to an understanding of the decimation of urban surface railway service – a catastrophe we call the Transit Holocaust, which precipitated the disastrous decline and marginalization of public transportation in the vast majority of North American urban areas. We strongly agree with Callie's contention that this disaster was not the "inevitable result of a natural evolutionary process", but rather the result of "government intervention that allowed automobiles to flourish at the expense of other transportation modes." In our Photo Gallery section, we note:

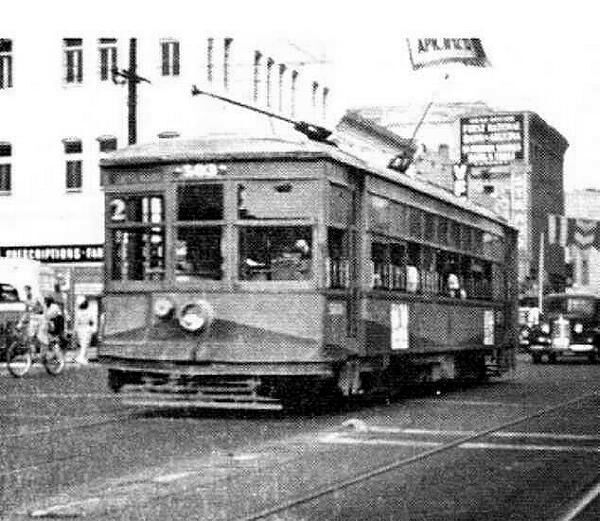

Opponents of modern-day mass transit, and rail transit investment in particular, point to the demise of electric streetcars as evidence that public transport has been rejected by the travelling public and has little to no future. Clearly, this is a serious misrepresentation of reality. Understanding the authentic dynamics of the past is critical to crafting and promoting viable solutions, such as light rail transit, for our future. Callie's analysis is reproduced below as it appeared as an op-ed in the Tucson Citizen newspaper. http://www.tucsoncitizen.com/index.php?page=opinion&story_id=102903b5_guesttransit Tucson Citizen Guest Opinion: Tucson mass transit has history of manipulation Mary Beth Callie Critics of mass transit sometimes contend that buses and light rail should not be subsidized by taxpayers. If transit is such a good idea, it is argued, the private sector would find a way to pay for it, and to operate the system for profit. What they disregard, however, is one of the primary roles of government is to support – through subsidy or regulation – the basic infrastructure on which commercial and civic life depend. For example, to ensure that citizens have reliable access to basic utility services, local governments issue franchises to private or municipal corporations. Beginning before the turn of the 20th century, most cities in the United States – including Tucson – granted franchise charters to mule-operated, and then electric, streetcar transit companies. When the automobile was first introduced, many Americans considered it a nuisance. But, by the 1920s and '30s, the "good road" movement had resulted in the United States heavily subsidizing its automobile infrastructure and related industries by building roads. The history of Tucson transit illustrates how our now car-centered culture is the direct result of those past investments and choices. In the mid-1920s, a 3-mile electric streetcar loop, operated by Tucson Rapid Transit Company (TRT), extended across the university and downtown area. In addition, TRT's bus line reached out to Campbell and Occidental Bus Company operated a competitive line in south Tucson. To some, TRT's buses and flexible routes seemed to usher in a new, modern era. In 1930, TRT petitioned City Council for changes in its city franchise, to substitute buses for streetcars on its transit system. For TRT, buses were more economical to operate, considering that they could be driven on roads paid for by the public; in contrast, to operate streetcars, the company had to pay the full cost of maintaining overhead power lines, tracks, and pavement. On Nov. 22,1930, the Tucson Daily Citizen editorialized that the time had rightly come for street cars to be "laid away in ceremonial lavender." The Citizen reflected on how "one knew one's neighbor in those good old days. Any fresh abrasion or contusion, a new wrinkle or new patch of gray, stood out clearly at each morning's examination of neighbor by neighbor across the aisle." But, streetcars, the Citizen wrote, were vestiges of the city's village phase, and that the prospects of a "track-bound tramway steadily shriveled" with the growth of Tucson and competition of automobiles. This substitution of buses for streetcars can also be explained by a less known story. Although commonly referred to as the "child" of Tucson Gas, Electric Light and Power Company, TRT was controlled by Cities Service Company of New York (now Citgo). Throughout the 1920s, this holding company acquired countless oil fields and filling stations, and become one of the most consolidated American corporations. In the context of City Services' expansion, TRT's petition takes on new significance: TRT's buses provided City Services with a predictable and expanding market for its oil supply. It was buses, not street cars, that depended on oil. That demand gave manufacturers strong incentives to modernize their buses, but not street cars. What happened in Tucson foreshadowed a subsequent national pattern. In the 1930s -1950s, General Motors, along with leading oil and tire companies, bought out and dismantled successful street car systems throughout the country, and lobbied for National Highway legislation (see www.newday.com/guides/takenforarideSG.html). In the coming week, Access Tucson (M-F, 10 PM, Channel 74/ Cox and Comcast) will air the film documentary, "Taken for a Ride," which chronicles this story.

This history reminds us that our automobile-centered culture is not the inevitable result of a natural evolutionary process. Tucson Rapid Transit, Cities Service, and GM depended on public investment. It was government intervention that allowed automobiles to flourish at the expense of other transportation modes. We continue to directly or indirectly subsidize our auto-centered culture today. In addition to the expensive road system, taxpayers underwrite police and emergency response that attends over 14,000 reported car accidents each year. Our widely available free or cheap parking is an often overlooked cost that is paid for with other taxes or with more expensive goods and services. Air, water, and land pollution caused by our dependence on automobiles adds to our public and personal medical expenses. As individuals, we pay the costs of gasoline and automobile purchase and maintenance. As taxpayers we pay billions for petroleum supply line policing and production subsidies. Since the late 1980s, our city leaders have continued to invest heavily in roads, particularly in the city fringe areas, while neglecting our bus system. Now, if we Tucson voters refuse to invest in an expanded transit system, we are in fact choosing to continue subsidizing the current auto-dependent system. Instead, we can choose to invest in an infrastructure that will improve quality-of-life for all Tucsonans. In doing so, we also gain the opportunity – as the Tucson Citizen described over 70 years ago – to meet our neighbors across the aisle, and to make Tucson a better place for future generations. Mary Beth Callie is an adjunct professor in the UA Department of Media Arts Media and Public Policy. Light Rail Now! websiteUpdated 2003/11/03 |

|

|

|